I’m going to start labeling these writeups differently. I feel conflicted, usually, like I should be writing more, that I should almost be writing a review or something. So now games I play and write about be will be labeled as part of my Game Journal. While I’ll try and still give a reasonable amount of context, I am going to write (especially for more well-known game) assuming the reader has at least some familiarity with the game.

Aged But Not Outdated

I’d imagine Spec Ops: The Line can be a challenging game for some people to go back to. Almost approaching a decade old, games have matured a lot in both gameplay and narrative. A big budget game trying to have a message is nothing surprising now (even if the execution is often questionable), and from 2021 eyes, something like Spec Ops: The Line could possibly feel too on the nose, too overwrought and even too obvious. But if you can look back with your brain in 2012 mode, Spec Ops feels well ahead of its time, speaking to the audience an Indie Game type punk attitude, audacious instead of overwrought in its earnestness.

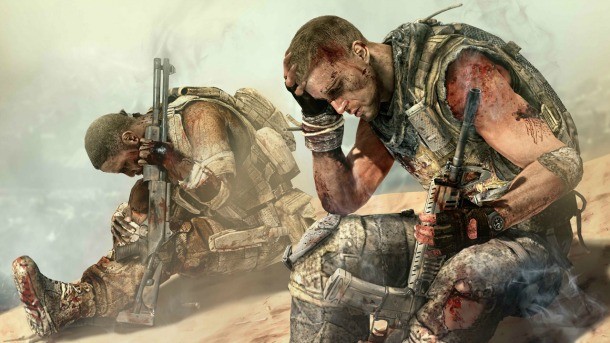

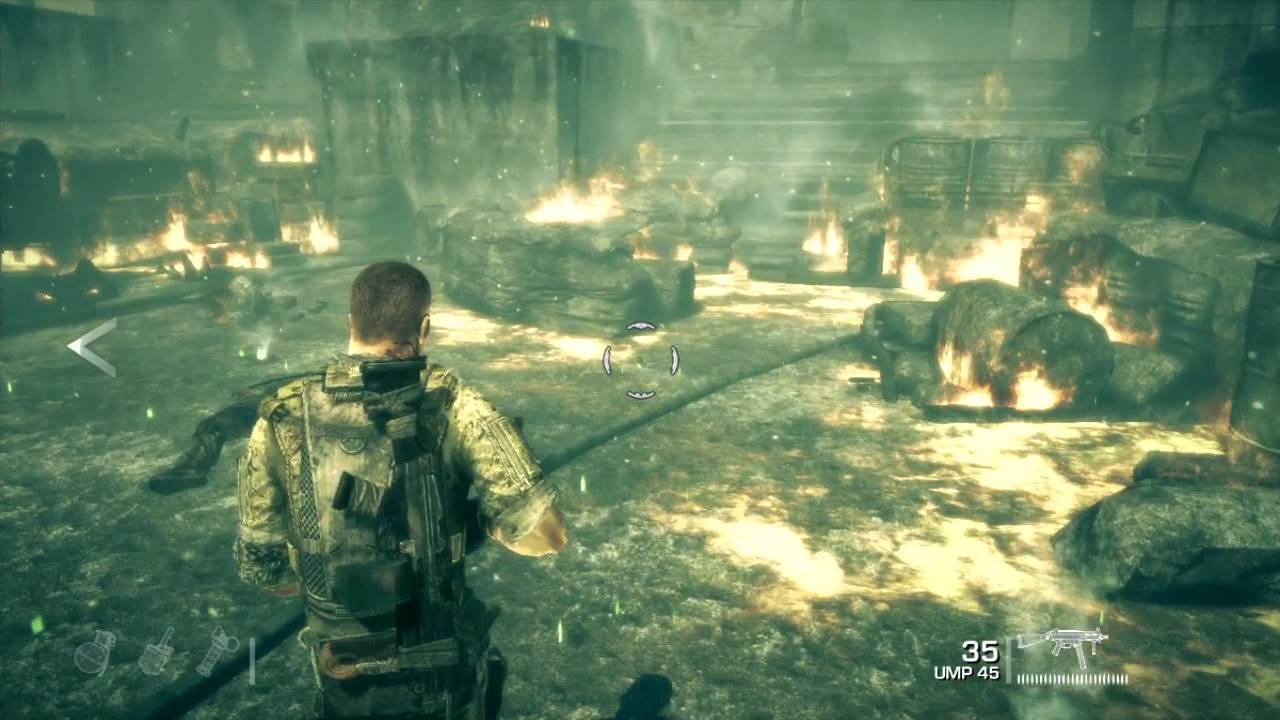

The game is also gorgeous. While little minor details can tell you when the game was made (I found myself fixated on one of my partner’s boots, with ‘shoe laces as a texture’) the game has aged remarkably well. Technology may grow old, but artistry survives. Beautiful setpiece shots and vivid colors. Before Mad Max: Fury Road, Spec Ops was the game showing the desert not as shades of brown, but as saturated and vibrant. Even the sand storms and violence cannot surpress the beauty of dubai and the game makes it clear you are in a place that once was and, in a way, still is beautiful.

The game’s almost otherworldly beauty is appropriate when matched up with the hallucinatory and trauma laden nature of the game. Despite constantly descending, you are constantly on top of huge buildings, confronted by scale and depth. It could almost be easy to miss, but the map layout is so unrealistically vertical that it comes off as some kind of mapmaking dutch angle. It’s not accidentally wrong, it’s purposefully uncomfortable. The characters are expressive, and how their bodies and demeanor change throughout the game doesn’t just serve to be immersive, but symbolically representative of the changes they’re feeling.

Third Person and Player Agency

A lot of Spec Ops discourse about the story has been done to death. If you want to know how Spec Ops communicates its distaste for heroic violence, there are many great deep dives you can read. But the thing I kept thinking about was the years of discourse about the game versus how I felt as I experienced the events in the game.

A common complaint is that the game blames you for things it forced upon you. That Spec Ops hates the player. That You Had No Choice. While this is thematically appropriate, my playing of the game didn’t feel so much like the game was forcing me and then rubbing my face into it, but instead like it was subjecting me to dramatic irony. Now don’t get me wrong, I think the game is perfectly excited for the idea that you might buy in in the same way Walker does throughout the game, but it is by no means required. From the first fire fight in the game, the voices in my head echoed ‘this feels wrong’. This wasn’t just an uncomfortable willingness for violence that one would expect from a 3rd Person military shooter. From the very beginning they identify that you are to make contact and then report back. But instead you dig deeper, and respond more violently, killing before asking questions that are clearly obvious to the player.

Do you buy in to Walker’s madness as your avatar or are you watching him, playing him like one would perform a morality play? The 3rd Person nature of the game makes things clear. You are not Walker. You might, for awhile, foolishly share his cause, but you are not him. You are watching his tragedy. How that tragedy reflects on the player is up to them.

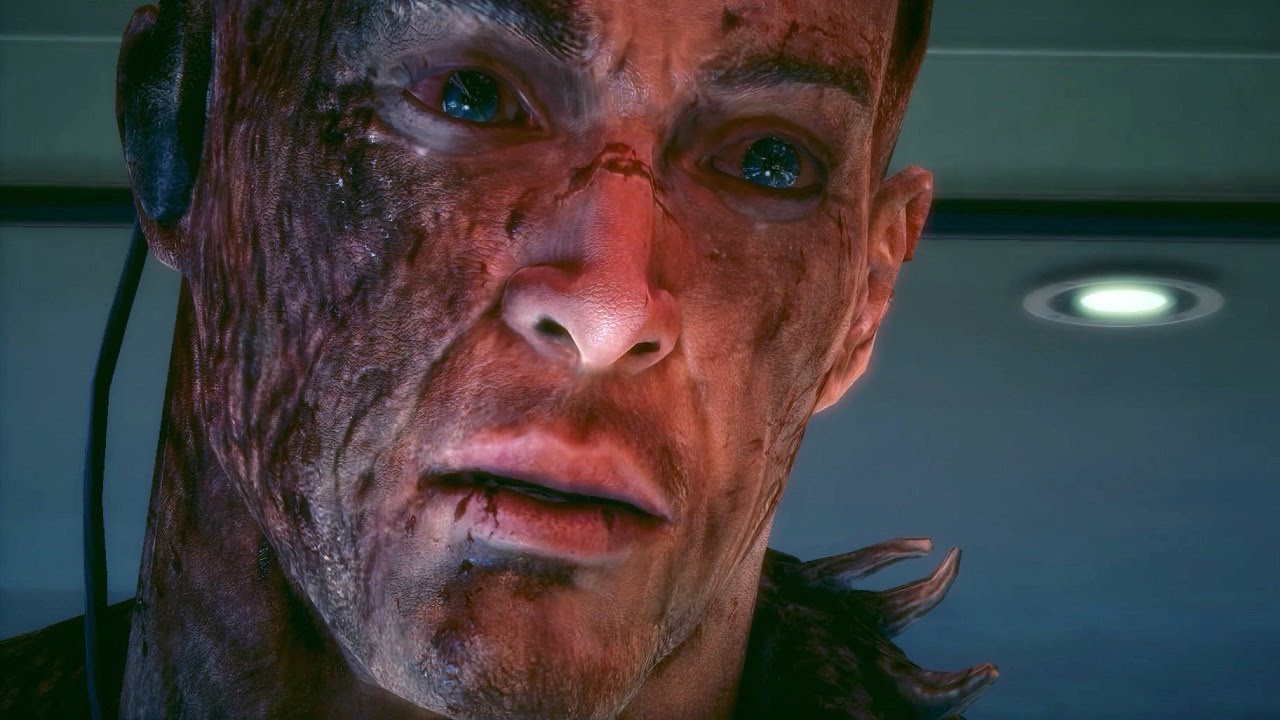

As the game progresses and Walker becomes more visibly scarred, as his eyes become emptier, the game forcefully separates him from yourself. His actions grow more violent. Your execution animations, which I avoided for most of the game due to feeling unnecessary, increase in sadism as things progress.. Another fun detail is that ammo is scarce in the game and enemies only drop based on what weapon they have equipped…

… Unless you execute them. This was Doom 2016 years before hand. Execute an enemy and you get ammo for all your equipped weapons. The game doesn’t want to punish you, it wants you to play the part in this tragedy.

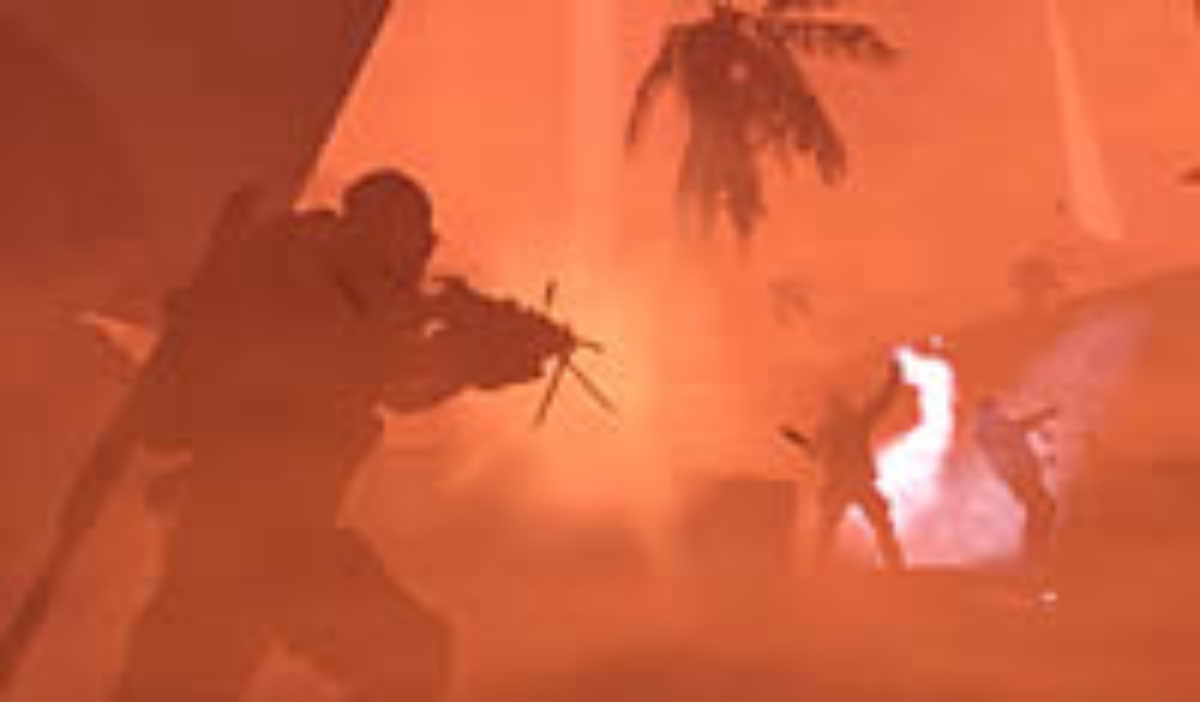

The White Phosphorus segment is chilling, harrowing and oddly beautiful. Many complain about the lack of choice, that they are forced to practically commit a war crime. The segment is gamified, throwing back to arcadey, indulgent Call of Duty segments, separating you from the violence. But are you separated? I feel this is a sign of how the game isn’t directly trying to judge the player.

The games tells you everything. It shows you what this stuff does. You know it’s horrible. Your subordinates debate the necessity. Walker makes it an order. You are (hopefully) not dropping blasts from the sky in a gleeful, guilt free haze of fun. You are waiting and cringing, fearful of what you’re going to see when you return to reality. The results are worse and then worse again.

The violence you unleashed is shown with an almost painterly artistry. This artistry is called back upon when the player gazes upon Konrad’s (or, as the Picasso quote goes, your) painting.

What’s interesting is the game gives you decisions. None of them matter, materially. The game doesn’t punish you or reward you. The decisions are either up to you, or up to your interpretation of Walker. Even come the ending, who does Walker blame? Can Walker return to a normal life, or is he consumed by violence, again, playing your part of the morality play. The endings are not a question of what you want to do, but how you contextualize the events you just saw.

Final Thoughts

I had this game sitting in my Steam library for years. It was gifted to me an eternity ago and I’m glad I finally got around to it. While the game is lacking as far as 3rd person shooters go, it’s gorgeous and the story, while heavy handed at times (with a few plot details that struggle under scrutiny), is chilling and memorable. There are many rich stories in games now, so while I won’t recommend it to everyone, it definitely has a lot to give to people who like to explore older titles.